The real reason consumers aren’t spending is not a matter of monetary policy; it’s a matter of psychology.

On June 2, the postman rang once — and, boy, did he ring.

That day, the Wall Street Journal published a strongly worded letter titled, “Grand Central: A Letter to Stingy American Consumers,” which included these notable passages:

“Dear American Consumer,

“This is the Wall Street Journal. We’re writing to ask if something is bothering you. The sun shined in April and you didn’t spend much money. The Commerce Department here in Washington says your spending didn’t increase at all, adjusted for inflation last month, compared to March.

“You’ve been saving more too. You socked away 5.6% of your income in April after taxes, even more than in March. This saving is not like you. What’s up?

“Fed officials want to start raising the cost of your borrowing because they worry they’ve been giving you a free ride for too long with zero interest rates. We listen to Fed officials all of the time here at The Wall Street Journal, and they just can’t figure you out.”

Well, on behalf of the “stingy American consumer,” we’d like to answer this letter to best of our ability.

“Dear Wall Street Journal,

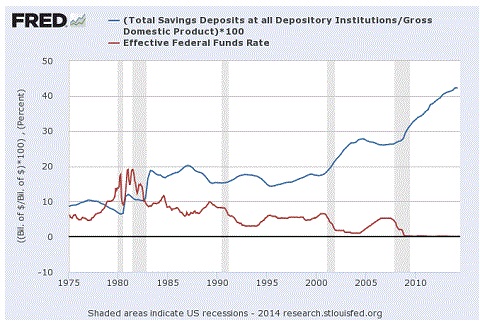

“Your frustration is well founded. Something is off. People have taken the Fed’s gift of free money and returned it to sender. This isn’t normal, as the chart of the total savings versus the Federal Funds rate since 1975 shows.

“Here you can see that for the better part of four decades, lower rates coincided with mild to steady savings… until mid-2000. Then, the pattern changed drastically. The cheaper it became to borrow, people borrowed less — a lot less.

“‘What’s up?,’ you ask? What changed to compel this radical shift toward thrift?

“In Chapter 9 of his business best-seller Conquer the Crash, Bob Prechter explains:

When the social mood trend changes from optimism to pessimism, creditors, debtors, producers, and consumers change their primary orientation from expansion to conservation.… consumers save more and spend less.

A defensive credit market can scuttle the [central bank’s] efforts to get lenders and borrowers to agree to transact at all, much less at some desired target rate.

During deflation, they cannot even induce them to do so with a zero interest rate.

“Deflation? Nobody said anything about the “D” word, but in fact, that’s exactly why consumers have gone on a buying boycott. Conquer the Crash writes:

These behaviors reduce the ‘velocity’ of money, i.e. the speed with which it circulates to make purchases, thus putting downward pressure on prices. These forces reverse the former trend.

“Note the emphasis on ‘downward pressure on prices.’ Here, our November 2014 Elliott Wave Financial Forecast shows you ample evidence of its arrival:

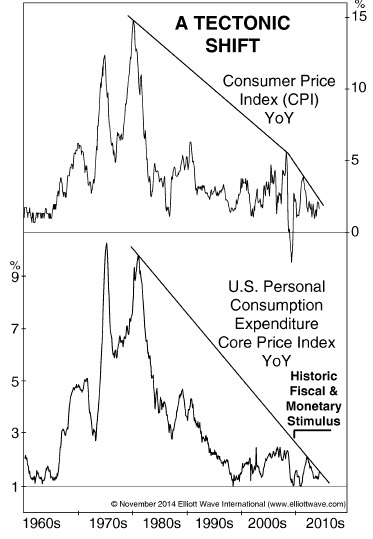

Most economists are baffled: ‘One of the greatest mysteries is why the U.S. has lacked inflation, despite all the money being pumped into the economy.’ This long-term chart of the CPI shows a succession of lower highs since the early 1980s, as inflation turned into disinflation, which is on the cusp of leading to outright deflation.

Some argue that the Consumer Price Index is rigged to show milder levels of inflation, but the bottom graph shows the same steady move toward the zero line in the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index, an alternate inflation measure favored by the U.S. Fed.

“Deflation is rare. Because of that, few people understand it. Deflation is also tricky, because it makes even the most ‘reliable’ financial assets to lose value, and those assets that no one expects to grow to actually gain.

“The ‘stingy’ consumer is not the cause; it’s the effect of a deflationary trend now underway in the world’s largest economy.”

Free Report

|