To understand the deflation problem, one must understand the nature of money and the amount of total debt in the US economy. In a credit based economy, money is created when banks make loans. Our money supply is not what Bernanke prints, but it is what we borrow. Fractional reserve banking coupled with interest based monetary system is the cause of Kondratieff Wave which defines the economic booms as well as the busts.

The Unpayable U.S. Debt

The widely reported $16.1 trillion federal debt is a drop in the bucket.

Financial transparency is a must for U.S. publicly traded companies. But if the federal government had to abide by those same regulations, more Americans would know that the often-reported $16.1 trillion federal debt doesn’t come close to the truth about the nation’s liabilities.

In a Nov. 26 Wall Street Journal opinion piece, a former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission and a former chairman of the House Ways & Means Committee write:

The actual liabilities of the federal government — including Social Security, Medicare, and federal employees’ future retirement benefits — already exceed $86.8 trillion, or 550% of GDP.

The authors say that few people know about the $86.8 trillion figure because that figure is not in print on any federal government balance sheet.

Federal debt is staggering enough. Municipal liabilities also pose a danger to the nation’s financial health.

Illinois has an unfunded pension liability of at least $83 billion. It had 45 percent of what it needed to pay future retiree obligations as of 2010, the lowest among U.S. states.

Bloomberg, Aug. 29

The article also noted, “California, with an A-ranking, one level below Illinois, remains S&P’s lowest-rated state.”

Budget shortfalls in California and Illinois are just the tip of the municipal financial iceberg. Many other state governments are financially swamped.

How did municipal spending get so out of control? Well, a stupefying story out of Bell, Calif., provides a hint. On Nov. 26, CNN reports that the Bell police chief earned $457,000 a year, and “He is now asking for more money.” In 2010, the Bell city manager resigned after controversy over his $787,000 yearly salary.

States Are Broke and Approaching Insolvency

… States’ legislatures continue to blow money. For years,

state governments have been spending every dime they could

squeeze out of taxpayers plus all they could borrow. (The

lone exception is Nebraska, which prohibits state indebtedness

over $100k. Whatever Nebraska’s official position on any

other issue, by this action alone it is the most enlightened

state government in the union.) But now even states’ borrowing

ability has run into a brick wall, because the basis of

their ability to pay interest — namely, tax receipts —

is evaporating. … The goose — the poor, overdriven taxpayer

— is dying, and the production of golden eggs, which allowed

state governments to binge for the past 40 years, is falling.

The only reason that states did not either default on their

loans or drastically cut their spending over the past year

is that the federal government sucked a trillion dollars

out of the loan market and handed it to countless undeserving

entities, including state governments.The Elliott Wave Theorist, November 2009

If there’s another leg of the economic downturn, expect a further dwindling of tax receipts.

Finally, consider the wobbly financial dominoes in Europe and what may happen in the U.S. after the first one falls.

|

8 Chapters of Conquer the Crash — FREE

Can the Fed Stop Deflation? Should you rely on the This 42-page report can help you prepare for your financial Get Your FREE 8-Lesson “Conquer the Crash Collection” Now >> |

Deflation and the Next Five Years of Financial Turmoil

The following is a sample from Elliott Wave International’s new 40-page report, The State of the Global Markets – 2013 Edition: The Most Important Investment Report

You’ll Read This Year. This article was originally published in Robert Prechter’s July 2012 Elliott Wave Theorist.

In the first five months of 2012, there were 20 times as many Google searches on “inflation” as there were on “deflation.” This is down from a ratio of 50 times in June 2008. If any theme has been overdone over the past six years, it is the theme of inevitable inflation if not hyperinflation.

Inflation reigned for 75 years, from 1933 to 2008. People are so used to it that they cannot imagine the opposite monetary environment. Bullish economists have been calling for recovery, which means more inflation, and bearish advisors have been calling for a crash in the dollar, which means hyperinflation. No wonder those are the terms on which most people have been searching.

But only one word allows you to make sense of what’s going on in the world, and inflation is not it. The secret word is deflation.

Deflation explains:

- why interest rates on highly rated bonds are at their lowest levels in the history of the country;

- why the velocity of money is the lowest since the 1930s;

- why huge sectors among investment markets are down over 40%;

- why the Consumer Price Index (CPI) just had its biggest down month since 2008;

- why Europe is in turmoil.

Here are some details: Ten-year Treasury notes pay out less than 1.5% annually, their lowest rate since the founding of the Republic. Treasury bills yield essentially zero, their lowest level ever. The velocity of money failed to rise during the past three years of partial economic recovery, and it recently made new lows. Real estate prices have fallen 45% in the past six years. Commodity prices — as measured by the CRB Index — are down 39% over four years. This group includes oil and silver, two of the most hyped investments of the past decade. Remember in March when articles quoted analysts calling for $5, $6 and $8-per-gallon gasoline? In just three months since then, gas prices have fallen 15%, knocking the CPI into negative territory.

Deflation also explains why European loans are at risk, why Germany is tapped out, why Greeks are protesting in the streets, and why U.S. corporations’ overseas profits are down. Deflation lets you make sense of the world.

What is deflation? Economists define it three different ways, but I find only one definition useful: Deflation is a contraction in the overall supply of money and credit.

Why must deflation occur? Answer: There is too much unpayable debt in the world.

As argued in Conquer the Crash, it ultimately does not matter what the authorities do; they can’t stop deflation. This prediction is being borne out. Since 2007, the Fed has monetized $2 trillion worth of debt; the federal government has borrowed another $7 trillion; and it has pumped out $1 trillion worth of student-loan credit. Yet real estate and commodities slumped 40% anyway.

These drunken-sailor-type policies have indeed succeeded in nearly maintaining the overall volume of money and credit.

But in the long run you can’t fight a systemic debt overload by piling on more debt. The Fed and the government are shifting the burden of trillions of dollars’ worth of debt obligations from reckless creditors onto innocent savers and hapless taxpayers. The ploy might work if the public’s resources were infinite, but they aren’t. Perhaps this policy temporarily prevented a series of big institutional disasters, but it was only at the ultimate price of a gigantic public disaster.

Such actions have become politically less palatable. Some observers realize that the student-loan program of lending at below-market rates is exactly the model the government used for housing loans, which ended in a spectacular bust. Others know that the government cannot continue to borrow at the current pace and expect to stay solvent. Politicians on both sides of the aisle are tired of the Fed’s bailing out of highly leveraged financial-speculation institutions.

But whether these policies continue or are curtailed is irrelevant to the outcome. If the government slows its borrowing, the overall value of debt will fall. If the government maintains or increases its present pace of borrowing, interest rates will eventually turn up, and the overall value of debt will fall. There is no escape from deflation.

Ironically, investors in the past decade have been doing exactly the opposite of preparing for deflation. Convinced of perpetually rising prices, they have bought every major investment. They chased real estate up to a peak in 2006. They bought blue chip stocks into the high of 2007. They pushed commodities up to a peak in 2008. They chased gold and silver up to highs in 2011. And through spring 2012, they continued to buy stocks and commodities on any rumor that promised inflation: European bank bailouts, Operation Twist, the Greek election, Group-of-8 summits, Fed meetings, Bernanke press conferences, improved economic numbers, predictions of QE3, central-bank interest-rate cuts, you name it. Meanwhile, the U.S. Dollar Index hasn’t made a new low for four years. During deflationary times, cash is king, and by far most investors have chosen to own anything but cash.

Deflation is still not obvious to the majority. Even now, most economists expect continued recovery, mild inflation and a rising stock market. But the essays on deflation.com are 180 degrees apart from conventional thinking. It may be too late for you to get out at the top, but there’s still time to learn how to sidestep the worst of the crunch.

People will be using the secret “d” word much more often over the next five years. By the end of that time, they will also be using its cousin “d” word, depression.

Two Signs That Deflation is Far From Over

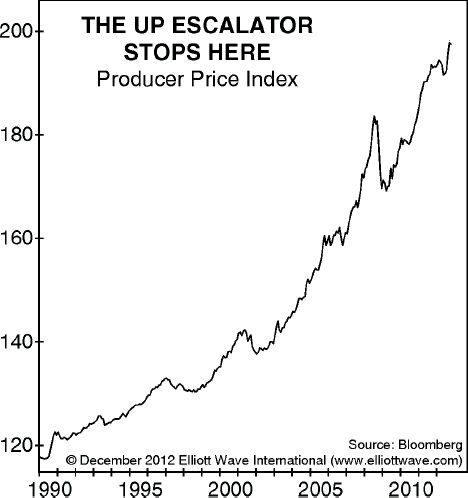

The federal government defines the Producer Price Index (PPI) as “the average change over time in the selling prices received by domestic producers for their output.”

With help from the Federal Reserve’s massive inflationary policies, the PPI has climbed even as the economy began to fall in 2008-09.

All the while, the financial media persisted with stories of an economic recovery. EWI analysts offer an independent perspective.

The New York Times declares, “Economic Gloom Starting to Lift.”

Corporate America, however, is not so sure. This chart of producer prices [wave labels removed] probably illustrates why. After years of largely uninterrupted growth, the Producer Price Index appears to be on the cusp of a critical reversal that should turn into a steady decline in wholesale prices.

The latest Financial Forecast published Dec. 7,

and the latest evidence reinforces the message of the chart’s

title. The PPI elevator has already descended to a lower floor.

The Labor Department said its seasonally adjusted producer price index slipped 0.8 percent last month, the second straight decline.

November’s drop in wholesale prices was the sharpest since May.

Reuters, Dec. 13

The Producer Price Index decline is happening in tandem with a notable reversal in consumer sentiment.

The Thomson Reuters/University of Michigan’s preliminary reading of the overall index on consumer sentiment plunged to 74.5 in early December, the lowest level since August.

It was far below November’s figure of 82.7.

Reuters, Dec. 7

The Federal Reserve’s machinations — which includes the Dec. 12 announcement of $45-billion in monthly Treasury bond purchases — will not stave off a developing deflationary trend.

In the second edition of Conquer the Crash (p. 114),

Robert Prechter describes what generally happens, depending

on the position of the Elliott waves, near the end of the

Kondratieff cycle.

Near the end of the cycle, the rates of change in business activity and inflation slip to zero. When they fall below zero, deflation is in force. As liquidity contracts, commodity prices fall more rapidly, and prices for stocks, wages and wholesale and retail goods join in the decline. When deflation ends and prices reach bottom, the cycle begins again.

Can the Fed stop deflation? Should you rely on the government to protect you? Get the answers you need now — free! See below for full details.