Think the Fed’s Emergency Rate Cut is Proactive? Think Again.

You might think that the Fed’s recent, unscheduled 50 basis-point cut in the federal funds rate is a proactive move that places the central bank at the vanguard of revolutionary uses of monetary policy. But that could hardly be further from the truth.

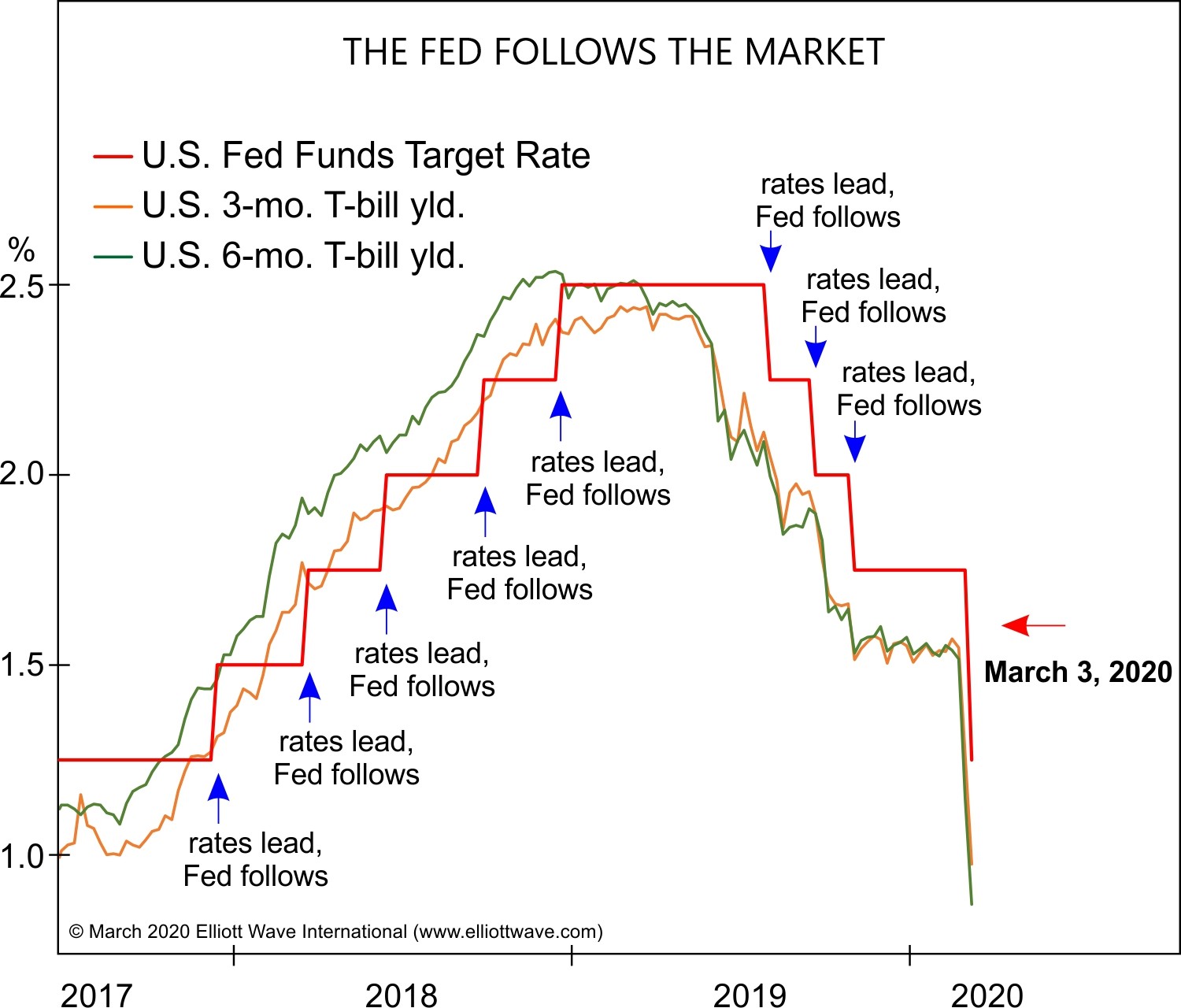

For decades at Elliott Wave International, we’ve observed that the Fed simply follows the yield on short-term government debt. We say that “the Fed follows the market” because the freely traded bond market determines the yield on government debt. The yield on short-term U.S. Treasuries started falling in earnest in February, and in March the Fed aligned its target rate with the trend of the market. There’s nothing radical or revolutionary about it. The Fed merely followed the market yet again. This chart shows the recent history.

Will the cut in the federal funds rate stem the bleeding in the economy? Will it halt the spread of the coronavirus? Will it have any impact on any financial market whatsoever? If you’re learning to think like an Elliottician, then you already know that the answer to each of those questions is “no.”

As Robert Prechter and his co-authors wrote in Chapter 3 of The Socionomic Theory of Finance:

The myths of central bank potency and interest-rate causality are so pervasive that conventional analysts cannot imagine a better explanation for trends in financial markets and the overall economy. But the interest-rate market is the dog wagging the central-bank tail, and neither of them determines risk preferences, stock prices or trends in the economy.

For most people, the idea that markets guide the decisions of central bankers rather than the other way around is counterintuitive. But no data show that financial prices change in reaction to administrative directives. On the contrary, these data expose the fact that administrators constantly monitor markets to decide what actions they should take.

Some theorists might try to argue that speculators in government debt are successfully anticipating central banks’ policy moves and adjusting market rates on government bills ahead of central-bank announcements. This is a variation of discounting theory, which Chapters 7 and 39 heartily challenge with respect to stocks and the economy. With respect to interest rates, which scenario is more likely: that central banks follow the market with approximately a five-month lag, or that investors follow central banks’ directives five months in advance? The latter claim would seem detached from reality on at least two counts: Prior to central-bank meetings, market observers and even trained economists typically express not foreknowledge but pervasive uncertainty about possible rate actions; and there is no evidence that central bankers know five months in advance what they themselves are going to do.

Read more of the myth-busting, causality-inverting, eye-opening chapter, “Central-Bank Policy Does Not Control Interest Rates; It’s the Other Way Around,” when you join ClubEWI for FREE. Sign up now and access it instantly.